You should always dress to impress clients, investors, and customers, because a winning sales pitch is not enough to seal the deal. A woman’s professional appearance needs to support her professional accomplishments… If your business attire is distracting because it is too sexy, drab, or colorful, your business contacts may focus on how you look, not on your business skills. (from “Personal Grooming Tips for Business Women” by Lahle Wolfe http://womeninbusiness.about.com/od/businessattireforwomen/a/groomingtips.htm)

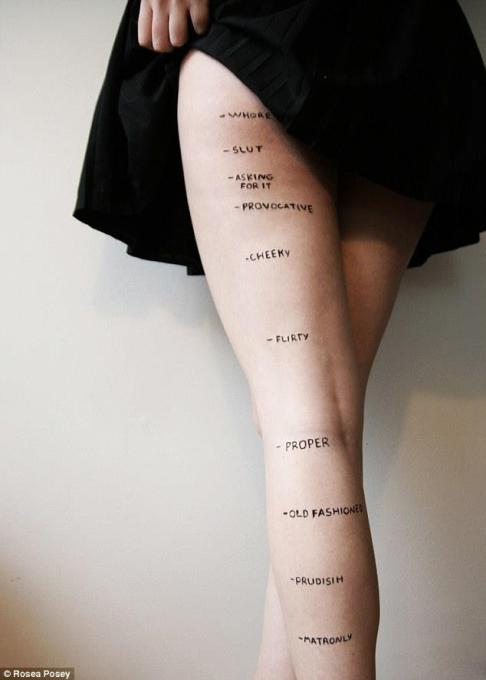

Women in most professions, but especially in male-dominated fields such as academia or business, walk a fine line. They balance the degree to which they express themselves relative to the expectations of their profession. Women’s bodies are expected to appear in a particular way, take up a particular space, and have a particular influence. These factors are defined and limited by standards which are read onto them.

As a matter of fact, many women harness and utilize fashion for various purposes, but not every woman is following the same rulebook, nor has the same degree of authorship over that rulebook. Some women don’t have the privilege, based on race, body type, class, and profession, to dress freely. Meanwhile, other women’s situation does provide them that opportunity to write their own rules. Nevertheless, both groups face criticism from society and must decide whether to go with the flow or to challenge that judgment.

Coming from a middle-class household, Em has seen the effect of privilege on how one feels they are allowed to dress–outside a professional context–firsthand. She related a personal anecdote: “My mother was incredibly concerned with weight and self-presentation, I learned that there was a specific way to dress to feel good, to feel “pretty”– one which could be easily accomplished, at least economically speaking. However, as the survivor of early (an on-going) childhood abuse and the oh-so-fun weight that came with puberty, I was not only left without many fitting pieces of clothing but also deeply ashamed of my body and what felt like my right to feel good about myself and dress the way I wanted (which was a combination of my mom’s “pretty” and my own style). I felt most safe in baggy clothes (often worn-out) that made me less likely to attract negative or shaming attention. A friend of mine at school, who came from a working class home once asked me why I dressed so “grungy,” when I had the resources to dress in much nicer clothing (the clothes that weren’t the schmata I wore every day, as my mother called them). This friend always dressed in a way that made her look slightly too formal, it seemed to me. She explained that she had been raised with the idea that one’s appearance should exhibit the potential for wealth or success– or, more generally, respectability. “I like to feel pretty,” she said to me once– which left me, who wanted to feel safe, confused. For her, the pressure of appearing “respectable” was greater than for me, who automatically had that privilege. On the flip side, she had the privilege of “feeling pretty,” with a supportive family and positive body image (for the most part), while I felt the need to appear in a way that made me “safe” and unexposed. A great deal of things we learned from our families, our culture, and our other experiences (potential and past) went into the simple act of getting dressed every day; an act which was meant to provide for us or save us from a particular outcome.”

In an interview with fashion blog ihearthreadbared.com, fashion expert and Gender Studies professor Tanisha C. Ford discusses how Africana women use style to “express their unique personas while also communicating something critical and important about race, gender, sexuality, class, and nationalist politic.” In other words, for women who have never been able to “check their race, gender, religion, or sexual orientation at the door,” getting dressed can be an act of agency and often radical self-expression. This act of getting dressed is “ordinary and intimate,” but also has “very real political and economic consequences,” writes Minh-Ha T. Pham of Ms. Magazine.

Though Ford spends most of her interview explaining how she and other Africana women use fashion to defy stereotypes about gender and race, she breezes past the implications of her fashion choices: by actively deciding to style herself one way, she is actively rejecting another way to style herself. She does not confront the implications for others as she gains voice and power through fashion.

As we read Ford’s article, the most troubling part for us was actually a comment by one of her readers who felt disappointed in Ford as she fails to exemplify the message she attempts to send. The interviewer’s last question relayed a personal anecdote about her first day as an Assistant Professor, and the conservative “all-black secretary outfit” that she regrets wearing. The reader found the interviewer’s disdain at the possibility of looking like a secretary and Ford’s lack of response to the comment offensive:

Wow. As I read this article, I was nodding my head in understanding and solidarity until I reached the passage, “I ended up in an all-black secretary outfit.” As a secretary at a university, I get the message, professor: denigrating me lifts you. While a casually offensive attitude to professional “lessers” isn’t a surprise, I expected better from someone who spends her days critiquing the politics of fashion and its impacts upon women. I guess, sometimes, the oppressor masquerades as the liberator.

This reminded us of Bordo’s article, in which she recounts losing twenty-five pounds in 1990. This was seen as a betrayal by some of her colleagues and students and she was then viewed as a hypocrite by some of her colleagues, given her work “Unbearable Weight.” “Although my weight loss has benefited me in a variety of ways, it has also diminished my efficacy as an alternative role model for my female students,” says Bordo in her book. As readers, we also feel that her choice of participating in a national weight-loss program weakened her credibility as a feminist who strives to minimize stereotypes caused by body beauty in society. This seems like a trade-off and also a dilemma for her; she needs to choose between appearing more physically attractive and being consistent with what she has been telling the world. Despite her assertion on how society should not discriminate against fat women, she, herself, is not a believer. Does she, too, discredit her greater message like Ford?

The division Ford creates between herself and the darkly-clothed secretary can be related to Nguyen’s idea about the distribution of beauty. In The Biopower of Beauty, Nguyen writes, “Distribution must imply beauty’s absence or negation by the presence of ugliness.” Beauty, it seems, is merely a comparative term. Its power is in its relation to ugliness, and one cannot exist without the other. Is Ford’s use of professional fashion to defy stereotypes of gender and race only powerful when it is compared to the “safe” all-black ensemble stereotypically associated with a secretary? Like beauty and ugliness, is power only powerful in relation to weakness? The commenter certainly felt weakened. Perhaps Ford’s fashionable empowerment, while meant to equalize the professional playing field by defying stereotypes, in fact shifted limited perceptions from one stereotype to another.

Another interesting link about “appropriate” dress for women, and how the clothes they wear has an influence on their success professionally: http://amdt.wsu.edu/research/dti/women/

reedh2013

April 7, 2013 at 1:07 pm

I was surprised by the comment by the reader of Nguyen’s blog. The secretary outfit is by no means reserved for secretaries today, so I thought it was interesting that she took the description of the outfit to be so offensive to her occupation in particular. Rather than saying anything negative about an all black secretary outfit, I think Nguyen was emphasizing the relative simplicity, understatedness and formality of the outfit compared to her graphic tee and yellow skirt.

In response to Bordo’s dilemma involving her weight loss, for me it doesn’t weaken her credibility as a feminist. However, it does illustrate one of the problems with Bordo’s theory as noted by Kathy Davis. In “Remaking the She-Devil: A Critical Look at Feminist Approaches to Beauty”, Davis writes that feminist approaches to beauty have neglected, “the problem of agency or remaking one’s body” (33). I agree with Davis that a woman should be able to do something for herself. Why should it be up to anyone other than the individual, feminists included, what self-improvements are appropriate and necessary? In addition, “self-criticism can be accompanied by a clearheaded feminist analysis of the structural constraints of feminine beauty” (Davis 35). So while Bordo expresses concern that her “own feeling of enhanced personal comfort and power means that [she] is…servicing an oppressive system” (30), I don’t think she must sacrifice her own comfort and feeling of empowerment in order to be effective and credible as a feminist, as a professor, and as a woman.

victoriadan

April 7, 2013 at 3:39 pm

I, too, was drawn to the secretary’s response, though I feel like her concern was legitimate. Some women do not necessarily have it in their power to be agents in their appearance (at least, they may not have other economically/socially viable choices when it comes to attire and appearance). A secretary, after all, not only has her “official” responsibilities, but she has her implied duties as a professional symbol and a status marker of a business. When we talk about work and fashion, we cannot forget the specific roles that women play and the different sets of expectations that go along with a job. Yes, I commend businesses that permit and encourage self-expression through clothing, and I think it is healthy to engage with your wardrobe, but I think what also needs to be discussed is why we feel the need to talk about clothes in the workplace if it is not particularly oppressive (ex: every woman has to wear a pencil skirt and modest heels). I think we have to discuss workplace and business culture comprehensively. What are the values of specific organizations? How do expectations of men and women differ within those organizations? Are there costs and benefits of aesthetic homogeneity versus total freedom over work attire? In general, I believe there is something to be said for fashion in the workplace, but we need to see the whole picture and all the perspectives.

eondich

April 7, 2013 at 4:38 pm

I agree that the secretary outfit struck me as being presented as inferior to a bolder look because it is formal and plain. Though Nguyen had the liberty to express her personality through clothing as a professor, she chose a more inexpressive outfit. I don’t think it would change the meaning of the question much if she had said she wore a black suit- “secretary outfit” simply happens to be her name for the ensemble.

I also was interested in the point about Bordo’s writing. Since reading the introduction to “Unbearable Weight” I have been curious about Bordo’s motives for losing weight, since she doesn’t elaborate on them and weight loss is often presented as being good for your health. Given the context, I assumed that she was thinking of her health, though I realize now that was presumptive of me. In any case, it’s interesting thinking about how the pursuit of beauty interacts with the ways we shape our bodies for other reasons. And how do Bordo’s motives shape her credibility? I think I agree with reedh2013’s arguments saying that the weight loss doesn’t challenge her credibility in the first place, but if we assume it does, do her motives or her actions matter more?

leafelhai

April 8, 2013 at 12:05 am

In all of these conversations about “appropriate” workplace attire, I couldn’t help thinking about the dress code of the hottest employer out there these days: Google. A job at Google not only entitles a person to a great salary, excellent benefits, and general prestige, it also gives him/her the right to wear jeans and a t-shirt to work (according to the internet, Google’s dress code is simply “you must wear clothing”). This example seems to challenge the notion of “dressing for success”; has the mighty Google managed to somehow break the iron-clad grip of society’s beauty standards in the workplace? Far from it. In fact, the phenomenon of high-powered elites dressing “down” is nothing new.

It’s a strange paradox: even though power puts a person in the spotlight and thus draws attention/criticism to their personal appearance, it also seems to be true that the more social power a person has, the less they need to establish or reinforce that power through their wardrobe. I’ve had multiple conversations here at Carleton with students who point out that the more money a student has, the more casual or even grungy they’re “allowed” to dress. These same acquaintances have remarked that students from less privileged backgrounds tend to take more effort with their personal appearance because they don’t want to be “pre-judged” as poor. As the authors of this post state, “Some women [and men] don’t have the privilege, based on race, body type, class, and profession, to dress freely.”

A hotshot Google programmer doesn’t need to wear a fancy suit to work because his/her prestige is so well-established that it needs no external reinforcement. Of course there are a lot of other factors at play here too– being casual is part of Google’s brand, and I know that the top executives of other big companies do still wear business attire. Furthermore, no woman, no matter how powerful she is, is given the freedom from wardrobe scrutiny that a man has. Still, this phenomenon is a nice lead-in to thinking about how class, not only race and gender, affects people’s ability to make free decisions about their self-presentation.

leafelhai

April 8, 2013 at 12:33 am

I posted this right before starting to read the Linda Scott piece. She makes a point near the beginning that’s relevant to my observations: “The social superiority of feminist dress reformers on dimensions of class, education, and ethnicity is recurrent. In every generation, the women with more education, more leisure, and more connections to institutions of power… have been the ones who tried to tell other women what they must wear in order to be liberated” (2). In other words, privileged women (like Google employees? Maybe…) tried to tell women without privilege that they should stop caring about their appearance when in fact, those women were in no position to make that decision without facing harmful effects.

blueebird

April 8, 2013 at 1:37 am

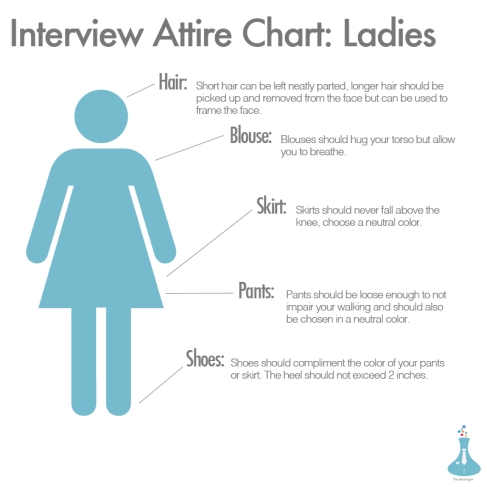

So I clicked on that last link and read the “Examples of Potential Women’s Interview Dress”. It is a fascinating article, however, there is also a male counterpart “Examples of Potential Men’s Interview Dress” (http://amdt.wsu.edu/research/dti/men/) and the comparison between the two is where things got really interesting. In the women’s article, there is often mention of how her hair looks or her choice in jewelry. There is constant mention of the woman’s body; a tight shirt makes one reviewer think “I’d expect to get hit with flying buttons during the interview! I’d conclude that she’d” and the woman had “recently gained weight and needed to go shopping for a larger size.” but the same reviewer thinks the tight blouse will have a different affect on a male interview (suggesting this is a woman reviewer!). On a different woman’s outfit, the reviewer’s actually commented on how the woman had chosen a great outfit for ‘her body type’. These people critiquing these women think they have the right to comment on each woman’s body type or whether or not it looks like the woman is trying too hard to be ‘trendy’. A short skirt all of a sudden makes a reviewer think the woman has ‘poor judgement’. These people are looking at women’s outfits and thinking they can make intimate comments about the woman’s body type or personality. It’s incredible. Reading the male article, you will find no such comments. Instead the reviewers go back and forth on whether a tie is too formal for an interview or not. There are no ‘negative’ comments on the most recommended outfit while the the most recommended woman’s outfit still has plenty of negative feedback, mostly about how her jacket looks too warm/long for the workplace. This is too short, this is too long; women just can’t win at all.

varanass

May 13, 2013 at 1:27 am

As a follow-up to this article, I came across this recent article, entitled, I’m Afraid My Curly Hair Is Holding Back My Career, published by Rachel Callman, on April 23, 2013 (http://www.xojane.com/beauty/is-curly-hair-unprofessional). In this xojane.com article, she explains that upon being hired for a job in the marketing industry, when on a road trip to a regional meeting with her boss, he informs her jokingly, “You know, you might not have gotten the job if your hair was curly at that interview. You look sort of girl-next-door. When it’s straight, it’s like, ‘Wow’. Isn’t life funny?” Her response, as expected, is composed at that moment in an enclosed space with her boss, although she was not showing her genuine emotion, which, according to her blog post, was mostly disbelief. For that reason, the next day she introduced herself at the meeting with her “natural, elongated Jew-fro out of spite.” Later, Callman explains that after moving to Los Angeles and interviewing for other job, she has encountered a similar problem, so she ensures that she straightens her hair in order to impress potential bosses (however sometimes she puts soft curls in her hair rather than her perhaps ‘tousled’ unprofessional hair which is apparently inappropriate).

When comparing her experience with that of the attached photo from the link at the bottom of the blog post from Washington State University, entitled, Examples of Potential Women’s Interview Dress. On the alleged spectrum of least recommended to most recommended, the woman that is least recommended has curly hair. An official in the Technical Field mentions critiques her, saying her hair reads as ‘messy’, when it looks like her hair looks like well-kept curly hair hairstyle. Both of these sources show that straight hair is preferred in the office as it exudes a more professional and put-together look.